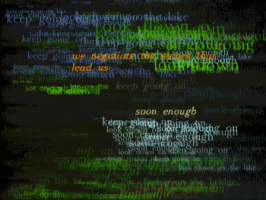

Paul’s Walk

This work was made in 2015, for instrument (or two instruments) and mac App (iPad or mac). The performer influences the way the visual and aural landscape emerges and recedes, and tells a story about a walk, a lake, and being in a place. Words are drawn from an informal text on a walk by Paul Roe.